With small tiles of marble and glass, Roman mosaicists created intricate mythological images, realistic scenes from nature, and other complex compositions to decorate the floors and walls of tombs, sanctuaries, and homes. Dalu Jones explores some mosaic masterpieces normally hidden in stores in Rome’s museums.

Like many cities, Rome was a hive of construction work between the late 19th and early 20th century as it put in place the many modern infrastructures needed for the capital of the newly unified state of Italy in 1871. To keep up with all this development, archaeological excavations were undertaken at a fast pace, unearthing large quantities of statues, furnishings, and floor- and wall-mosaics that once decorated ancient Roman houses and public buildings. Though there were many magnificent finds, not all of them went on view in the city’s existing museums; many, due to a lack of adequate spaces in which to exhibit them, ended up being stored in different warehouses. Only for a decade, between 1929 and 1939, were they shown to the public at the Caelian Antiquarium, which was subsequently closed. Mosaics recovered from their original locations in the excavations were especially awkward to move and remained out of public view until relatively recently. But today, some of the mosaics and other objects from this outstanding set of finds are on display at the Centrale Montemartini, a superb venue that reflects the modernisation that surrounded the uncovering of many of the artefacts it now houses.

Polychrome wall mosaic showing a harbour and ship, found in the garden of Palazzo Rospigliosi-Pallavicini in 1876, during construction work on Rome’s Via Nazionale. Late 2nd / early 3rd century. IMAGE: Rome, Musei Capitolini, Antiquarium.

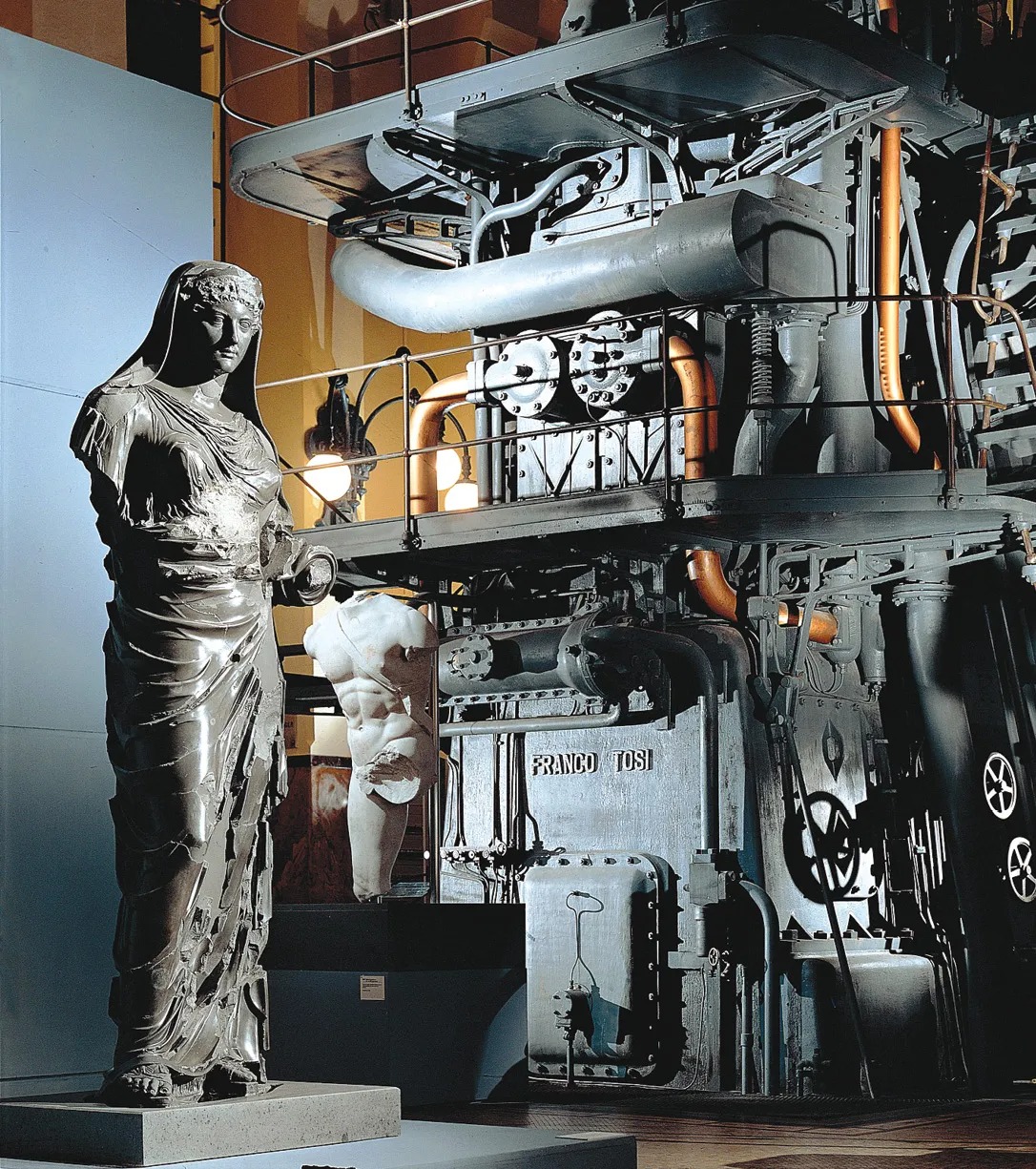

The Centrale Montemartini had originally been the first public electricity plant in Rome, in operation between 1912 and the mid 1960s, but was long in disuse. The space filled with ancient art that visitors can enjoy today is the result of a brilliant decision taken by the administrators of Rome’s Capitoline Museums to convert the former power plant into a museum during the renovation of the main museums. At first, the Centrale Montemartini was devised as a temporary exhibition space in 1997, but after the success of that exhibition it opened as a permanent museum in 2001, where some four hundred sculptures, reliefs, and mosaics dating from the Republican to the Late Imperial era, all found in Rome, can now be seen. Like London’s Tate Modern, which opened in 2000, Centrale Montemartini places art in an industrial setting, but, unlike the Tate, the hefty iron machinery is still in place. Thus, classical archaeology and industrial archaeology were combined in a bold design whereby the pre-existing machinery and the ancient objects on display were each to be a foil for the other. The dark rows of huge turbines and enormous pipes are an excellent background for the exquisite white marble statuary and polychrome mosaics on display and make the Centrale one of the most rewarding and unexpected cultural and artistic experiences in the city: the unusual contrast is memorable and effective.

The power plant’s expansive spaces make it possible to display monumental sculptures and reconstructions of architectural structures, such as the 5th-century BC pediment of the Temple of Apollo Sosianus, which once stood in the Campus Martius and was redesigned by Gaius Sosius in the 1st century BC (giving the temple the name Sosianus), and a huge 4th-century AD mosaic filled with energetic scenes of men with dogs and horses hunting boar and stags. This mosaic was found on the site of the lavish villa and garden complex of the Liciniani family, the Horti Liciniani, in 1903 during work on a railway embankment near the church of Santa Bibiana on the Esquiline Hill. Measuring 15m long and 9m wide, the mosaic can now be taken in in its entirety from a balcony in its current home.

Other outstanding examples of this dazzling ancient craft not usually visible to the public, as they are stored in various institutions across the city, are now on view in the exhibition Colours of the Romans: Mosaics from the Capitoline Collections. The exhibition affords the opportunity to rediscover many of these almost forgotten mosaics and see them next to those already displayed in the Centrale Montemartini. They date from the 2nd century BC to the 4th century AD and so chart the technical evolution of Roman mosaics over time, showing the extraordinary and consistent skill of the craftspeople who made them despite changes of fashion and patronage.

Mosaics were ubiquitous and would embellish the floors and walls of the mansions of the rich Roman upper classes and the houses of the middle classes who could afford them, as well as public buildings and funerary monuments. Although expensive, they could last more than a lifetime and were easy to clean and maintain. They show the widest range of decorative motifs, from geometric compositions to realistic renderings of vegetation, from portraits and representations of the everyday lives of the inhabitants of Rome to scenes from mythology and symbols of both pagan and Christian cults. Popular subjects were gory hunting scenes, views of the river Nile with its exotic wildlife, seascapes with different kinds of fish and marine creatures, and somewhat surreal and extremely detailed, lifelike trompe l’oeil depictions of the debris of banquets strewn on the floor – a sign of wealth and abundance and the transience of all things – called asaroton (Greek for ‘unswept floor’). As mosaics were just one of the means by which the wealthy could furnish their abodes, they are – where possible – shown together with the wall-paintings and sculptures that formed part of the same building’s decorative scheme. Extensive archival documents, historical photographs, and watercolours and drawings made at the time of the excavations detail the modern discoveries of the mosaics and their associated finds.

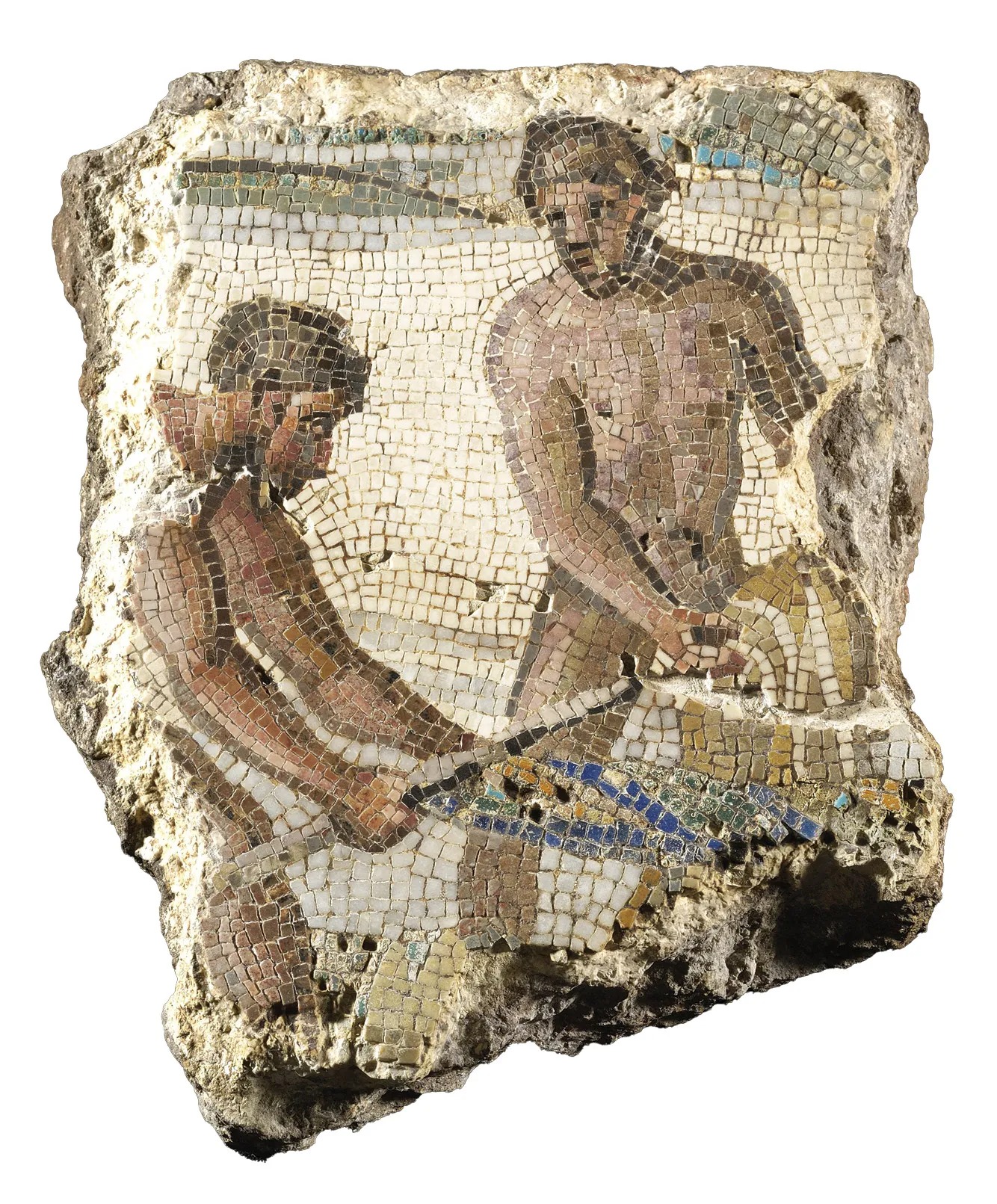

BELOW Polychrome mosaic showing fishermen at work, found in 1875 between the Via Labicana and Via Merulana in Rome. Late 1st / early 2nd century AD.

Polychrome mosaic showing fishermen at work, found in 1875 between the Via Labicana and Via Merulana in Rome. Late 1st / early 2nd century AD. IMAGE: Rome, Musei Capitolini, Antiquarium.

Originally, floor-mosaics had evolved from the pebble ones that used stones collected from beaches and riverbanks that were then set into cement. They could be monumental, like the grand 4th-century BC compositions found at Pella, in northern Greece, celebrating Alexander the Great. Pebble mosaics also made use of semi-precious stones, glass fragments, and strips of lead or clay to mark the outlines of the figures. Later, various techniques were employed by Roman mosaicists to design floor- and wall-mosaics according to the requirements of their commissioners. Widespread techniques include opus tessellatum – where larger tesserae (square pieces of marble, stone or glass, between 0.5 and 1.5 cm2) were positioned as close as possible into a freshly prepared mortar base to make up simple regular patterns, mainly for pavements – and the more intricate opus vermiculatum (vermiculatum meaning ‘worm-like’) that used smaller pieces, particularly of coloured marble or even more precious materials, to create subtle pictorial effects and higher levels of detail. Gradually, when advances in the manufacture of glass and the opening of quarries of coloured marbles made these materials cheaper and more readily available, complex designs for floor-mosaics became common features in buildings all over the Mediterranean world. Smaller and smaller tesserae, even minuscule ones of 1mm, were used for images of the utmost intricacy, including wall-mosaics that imitated famous paintings by prominent Greek and Roman artists. This incredibly painstaking and time consuming micro-mosaic technique is believed to have been invented in ancient Egypt and was first used for jewellery and small inlaid objects.

Wall-mosaics were developed by the Romans and may have derived from the fashion of decorating artificial grottoes and nymphaea (shrines to the nymphs) of villas and gardens of the Late Republican period (2nd-1st centuries BC) with pumice, coral, marble flakes, and reflective pieces of glass with rough surfaces and jagged edges, as well as shells – almost exclusively those of the cockle and the spiny-dye murex. The schemes chosen for these interiors – mostly mythological scenes with depictions of nymphs and the Muses, as well as sculptures of them – were enhanced by the use of water to create shimmering effects over the colours of the many translucent tesserae. The same play of water over decorated niches would be copied in Late Renaissance architecture when artificial grottoes were an elaborate feature of palaces and villas. While the origin of the term ‘mosaic’ remains uncertain, it has been suggested that it derives from the adjective musivum, ‘of the Muses’, referring to these specific designs featuring Muses and nymphs.

RIGHT Polychrome mosaic showing a Nilotic scene, found in 1882 in Via Nazionale. Second half of the 1st century BC. IMAGE: Rome, Musei Capitolini. Photo: Fabia Brunori.

Between 1875 and 1901, during the construction of one of modern Rome’s busy thoroughfares, the Via Nazionale, a number of rooms of a rich aristocratic residence on the southern slopes of the Collis Mucialis, a height on the Quirinal Hill, were discovered. The ancient structures included a nymphaeum from which three exquisite wall-mosaics were detached. The property – in the garden of the 17th-century Palazzo Rospigliosi-Pallavicini – may have belonged to the Claudii Claudiani, a family of senatorial rank, whose presence in the area is attested by the pieces of water pipe marked with their name. One prominent figure from this family was Claudius Claudianus, a distinguished politician of North African origin, who held numerous important positions during the reigns of emperors Septimius Severus and Caracalla, in the late 2nd and the very first years of the 3rd century AD. The grand wall-mosaic from the site – made of deep blue, red, white, and clear glass tesserae – shows a harbour with a lighthouse and a large ship; this is probably a reference to Claudianus’ commercial activities, since he was engaged in trade between Italy and Egypt. The wealth of Claudianus and his discerning taste are also evident from the choice of sculptures and beautiful pieces of furniture that have survived from his house and are on display to the public for the first time next to this mosaic.

Detail of an ornate mosaic border with birds and other creatures, found in 1888 near Via Panisperna. 1st century BC. IMAGE: Rome, Musei Capitolini, Centrale Montemartini. Photo Fabia Brunori.

Wall-mosaic with sea shells and glass and marble tesserae, found during work to open the Via dell’Impero. Mid 1st century AD. IMAGE: Rome, Musei Capitolini, Antiquarium.

The energetic building of the new Italian capital inevitably entailed real estate voracity and the destruction of noteworthy buildings and parks. One of these was the 18th-century Villa Casali on the Caelian Hill, which was demolished at the end of the 19th century to make way for a military hospital. Some of the works of art collected by the villa’s one-time owner, cardinal Antonio Casali (1715-1787), were lost, while others – like the famous Casali Antinous found between 1698 and 1704 in the grounds of the villa – were exported abroad; this superb 1st-century AD marble statue of the beautiful youth Antinous posing as Dionysos is now in the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen. Archaeologists fortunately managed to record and save some of the artefacts they found here before demolition obliterated all. Among them is a large floor-mosaic divided into 20 sections, each containing a different decorative motif.

Excavations at Villa Casali took place in the late 19th century, and again, more recently, in 1997. During the 19th-century work, an intriguing black and white floor-mosaic was found within a porticoed space surrounded by various rooms. The remains of these rooms are still visible in an inner courtyard of the hospital today. This mosaic was divided into two distinct parts: one with an epigraph within a tabula ansata (a formal frame with handles) and the other with an intriguing figurative scene. The larger part of the mosaic, made with small marble, limestone and glass tesserae, consists of the striking figurative composition, which shows an eye surmounted by an owl being pierced by a lance, while surrounded by fierce felines, a goat, a bull, a scorpion, a snake, and birds. This is an apotropaic image that served to ward off the evil eye that Greeks and Romans believed could cause illness and death.

Polychrome floor-mosaic with 20 sections, each with a different motif, found in 1886 during the demolition of the Villa Casali. Mid 1st century AD. IMAGE: Rome, Musei Capitolini, Antiquarium.

From the inscription, which reads ‘To those who enter here and to the Basilica Hilariana, may the Gods be propitious,’ we know that the mosaics come from the Basilica Hilariana. This was a religious complex housing priests of the somewhat obscure sect that worshipped the Phrygian goddess and protectress of the city, Cybele – also known as Magna Mater (great mother) by the Romans – and her husband Attis. The basilica was built in AD 145-155 and was named after one of Cybele’s worshippers, Manius Publicius Hilarus, a wealthy pearl merchant who paid for its construction. The portrait of this generous donor and the base of his statue were also found at the entrance of the basilica, whose excavation was carefully documented at the time, including through watercolours.

As well as homes for the living and places of worship, mosaics also adorned dwellings for the dead. Mosaics from 2nd- and 3rd-century AD tombs found outside the capital’s walls feature decorative motifs that are clearly symbols of death and eternal afterlife. These funerary mosaics make use of a somewhat repetitive repertoire of images derived from standard patterns that were revised and adapted by the mosaicists carrying out each separate commission. Tiled wreaths of flowers and fruits were commonplace, reproducing the floral offerings that decorated the tombs during ceremonies dedicated to the dead. The everlasting cycle of the annual seasons – each personified and identifiable from their seasonal produce, for instance flowers for spring and grapes for autumn – also appeared frequently.

LEFT Black and white floor-mosaic with an apotropaic scene warding off the evil eye, from the Basilica Hilariana, found in the 1880s during the construction of a military hospital on the Caelian Hill. Mid 2nd century AD.

Black and white floor-mosaic with an apotropaic scene warding off the evil eye, from the Basilica Hilariana, found in the 1880s during the construction of a military hospital on the Caelian Hill. Mid 2nd century AD. IMAGE: Rome, Musei Capitolini, Antiquarium.

BELOW Polychrome octagonal mosaic with peacocks, found in a tomb along the Appian Way. 2nd century AD.

Polychrome octagonal mosaic with peacocks, found in a tomb along the Appian Way. 2nd century AD. IMAGE: Rome, Musei Capitolini, Antiquarium.

Another symbol of eternity found in tombs is the peacock; as it sheds its colourful tail every year only to grow it again in spring, the bird came to symbolise regeneration beyond death. The magnificent birds, associated with the goddess Juno, are seen in the central motif of an octagonal polychrome mosaic from the floor of a 2nd-century AD tomb that stood along the Via Appia. Detailed panels, or emblemata, like these, made of smaller tesserae, were quite often inserted as centrepieces into large mosaics made of coarser tesserae. The tomb’s inner chamber has survived in particularly good condition as, after its vaulted roof collapsed, it was filled with earth. This rectangular brick chamber was decorated with mythological wall-paintings, while the floor, as shown in a watercolour executed at the time of the discovery, was covered in a mosaic that also included large borders with rectangular and rhomboid coffers.

Marble funerary relief for a mosaic-maker, found at the necropolis of the Isola Sacra near ancient Ostia. Late 3rd / early 4th century AD. The relief shows craftsmen at work cutting tesserae to set into a mosaic. IMAGE: Ostia, Antiquarium at the Parco Archeologico di Ostia Antica. Photo Fabia Brunori

What is quite extraordinary in all these different mosaics is their vividness and painterly quality, their kinetic effect, and the evident astonishing skill of their makers. The rendering of light and shade, subtle nuances of colours, lively facial expressions depicted with a few incisive lines, and the wonderful treatment of volume – not by means of brushstrokes but simply by small tiles of a comparatively limited number of colours – is continuously surprising.

The selection of artefacts on display at the Centrale Montemartini comes together to create a memorable synthesis of Roman art, which finds in floor- and wall-mosaics one of its highest and most refined expressions of technical ability and artistic inspiration. The Colours of the Romans exhibition is a feast for the eyes in the most unexpected setting, but even without it, the Centrale Montemartini – rarely explored by overseas visitors – remains a fascinating museum and well worth seeing, home to one of the finest permanent collections of ancient sculpture in Rome.

Leave a Reply