Ramesses I was born Pa-ra-mes-su to a noble Nile Delta military family. His father, Seti, was a military commander, and his uncle, Khaemwaset, was an army officer married to Tamwajesy, the matriarch of Amun’s Harem. He was born during the Amarna Period, which was a turbulent time in Egyptian history.

After the death of Pharaohs Tutankhamun and Ay, General Horemheb took the throne, making Ramesses I his vizier. He had several other titles such as:

“Chief of the Archers, Master of the Horse, Commander of the Fortress, Controller of the Nile Mouth, Charioteer of His Majesty, King’s Envoy to Every Foreign Land, Royal Scribe, Colonel, General of the Lord of the Two Lands, Chief of the Seal, Transporter of His Majesty, Royal Messenger for all Foreign Countries, Chief of the Priests of all Gods.”

Horemheb had no children so he was in search of an heir, which is found in Ramesses. This may be because Ramesses already had a son, Seti I, and grandson Ramesses II so that the rule will stay in the family. Ramesses then became the “prince of the whole country, mayor of the city, and vizier,” as it is stated on a statue of him found in Karnak.

As mentioned, Ramesses I married a woman named Sitra who also came from a military family. They had one son, who would later become Pharaoh Seti I. He probably rose to the throne when he was in his 50s, which was quite old for an ancient Egyptian king. His prenomen was Menpehtyre, meaning “Established by the strength of Ra,” though he preferred to use his personal name Ramesses, which meant “Ra bore him.”

Ramesses I only ruled for about 16 or 17 months, either from 1292-1290 or 1295-1294 B.C.E. During his reign, he probably took care of domestic matters, while his son was in charge of undertaking military operations. Ramesses was able to complete the second pylon of Karnak Temple, which was started by Horemheb. He also ordered the provision of endowments for a Nubian temple at Buhen.

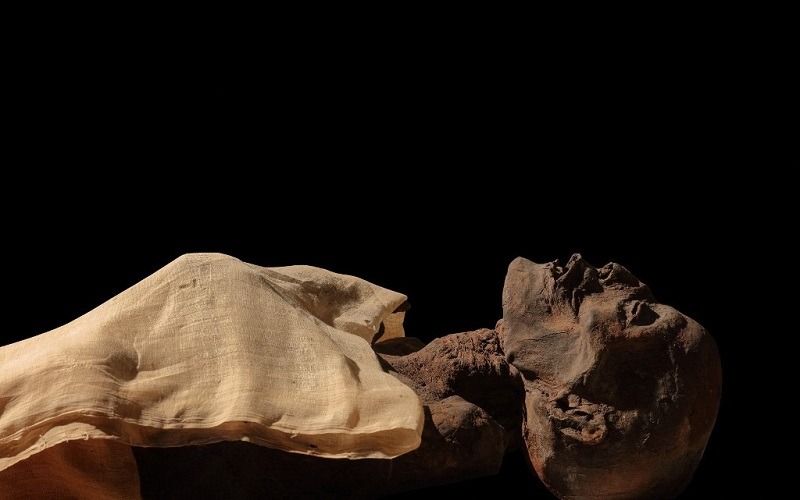

In the late 1990s, a cadaver was discovered that possessed many characteristics of a regal mummy, potentially Ramesses I.

Dr. James Douglas purchased this sarcophagus in 1861 and transported it to the United States. It was subsequently sold to Colonel Sidney Barnett, the son of the museum’s and hall of fame’s founder. The mummy remained in the museum for the next 130 years, identified as one of Akhenaten’s probable spouses, perhaps Nefertiti?

In 1985, a German technician named Meinhard Hoffman convinced a German television station to examine the mummy scientifically. Dr. Anne Eggebrecht examined the cadaver and initially determined that it belonged to a male. Dr. Wolfgang Pahl and his assistant Lisa Bark observed a number of characteristics consistent with one of the missing New Kingdom mummies, including crossed arms and clasped hands. The museum also contained a sarcophagus from the late 18th or early 19th dynasty.

The museum failed in the late 1990s, and the Michael C. Carlos Museum at Emory University purchased the Egyptian antiquities for $2 million. The mummy underwent CT scanning and carbon dating at this location. On the basis of CT scans, x-rays, cranium measurements, radiocarbon dating, and the general appearance of the mummy, it was postulated that it was Ramesses I’s cadaver.

This most likely means that the Abu-Rassul family who found DB320 in 1871 (and thus put many items out on the antiquities market for years without detection) may have found the tomb almost 11 years earlier. It is thought that Ramesses I’s mummy was taken by the family and sold in 1860.

Based on all the evidence, the Egyptian government requested the mummy be returned to Egypt. It was returned on October 6th, 2003, and is now located at the Mummification Museum in Luxor, Egypt. Not all scholars agree that this is Ramesses I, but agree that it was a noble from the 18th or 19th dynasty, maybe even the mummy of Horemheb.

The mummy in question is 1.60 meters tall and died when he was 35 to 45 years old. It is very well preserved for his perilous journey. An incision was made in the left abdomen through which the internal organs had been removed and replaced with linen packing. The brain was extracted through the nose and the skull was filled with liquid resin. These are all typical of the late 18th and early 19th dynasties.

Leave a Reply