An remarkable, albeit macabre, collection of mummified remains from various periods in the region’s history.

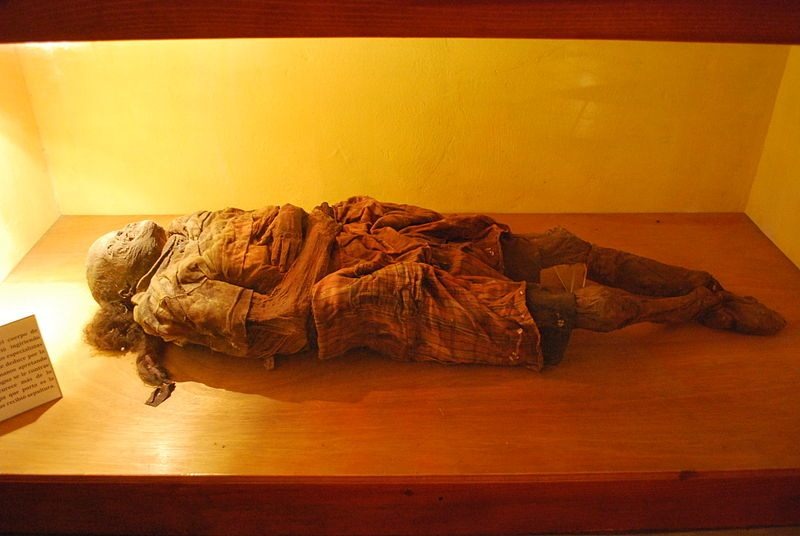

The 19th-century mummified remains of an unknown woman.

THE MUMMY MUSEUM IN THE small town of Encarnación de Díaz is a morbid collection that seems to have been ripped straight from the pages of famed Mexican writer Juan Rulfo’s gothic magical realist novel “Pedro Paramo.” On display are a number of macabre mummified remains whose disturbing stories are a testament to the darker side of Jalisciense history: a grimacing guerrilla gunned down by a gung-ho firing squad, a shawled señora with a sinister skeletal smile, a poisoned pariah, and a murdered miner, to describe but a few.

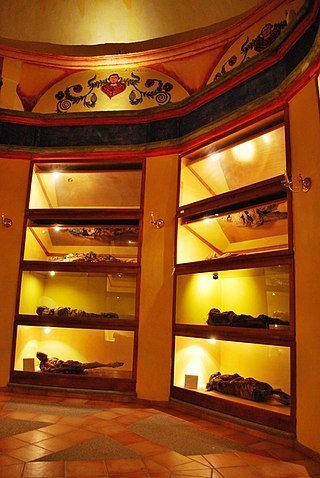

The mummy room.

The vault of the mummies.

The majority of the mummified remains, as evidenced by their clothing, belonged to residents of the town and its environs during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. One corpse belonged to a woman who was likely poisoned by rats, while another belonged to a man who was assassinated by outlaws who took gold ingots he had discovered in a mountain stream. The museum also asserts that two of its skeletons are considerably older and may have belonged to the Cacaxane people, who once inhabited the Sierras of Jalisco.

The mummy of Don Pedro Liebres who was reputedly killed by bandits after finding gold in the mountains.

The haunting mummy of a 19th-century woman.

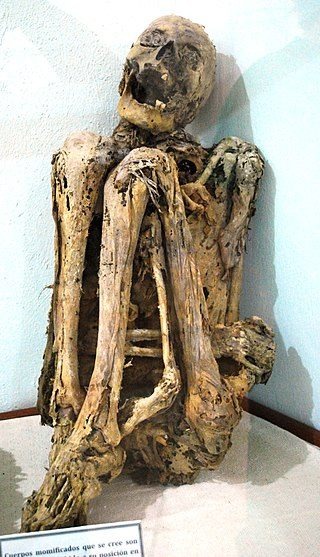

The funerary rites of the Cacaxane were highly unusual in Mesoamerica. The tribes buried bodies in graves known as “shaft tombs,” where the corpse would be interred in either a standing or cross-legged position. The aridity of the region and this burial practice were notably ideal for bringing about the mummification of human remains. But because the Cacaxane were driven to extinction by the Spanish conquistadors in a genocidal combination of disease pandemics and war, it remains a mystery whether the tribes buried their ᴅᴇᴀᴅ in this way intentionally to create mummies or whether this occurred as a natural process.

The mummy of the “Cristero” guerrilla (and his rifle) executed by firing squad in the early 20th century.

The face of the mummified Cristero guerrilla.

Many more of the displays in the museum are from the time of the Cristero rebellion, a Catholic insurgency that took place in the post-revolutionary period of the 1920s. The revolt was a response to the secular Mexican government’s attempts to end the political grip wielded by the Catholic church in rural areas of central western Mexico. The war proved to be a particularly bloody and protracted conflict in the Jalisco region, where strong Catholic beliefs and traditions were held by the majority of the Jaliscience population, who refused to submit to the centralized authority of the government.

One of the alleged pre-Hispanic Caxcane mummies.

The alleged pre-Hispanic mummies.

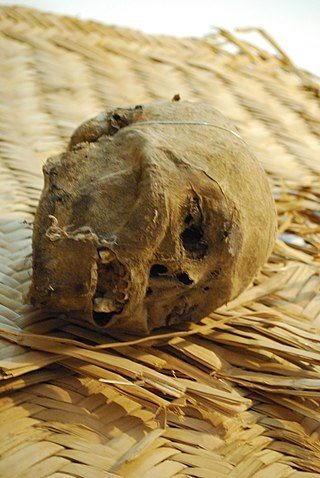

Mummified skull on a palm frond mat

The subsequent occupation of the region by government troops led to huge numbers of young men of the Catholic faith joining the “Cristero” guerrillas. The brutal treatment by government soldiers and the frenzied and fanatical rhetoric of clandestine priests convinced many that the apocalypse was nigh and that the president of Mexico was the devil.

The mummy of a woman who apparently died after mistakenly ingesting rat poison, 19th century.

The mummy of Macaria Delgado, 20th century.

The face of the mummy Macaria Delgado, a woman who died in the 20th century.

It’s estimated that between 30,000 and 50,000 people lost their lives during this four-year war, and some scholars believe the death toll was in fact much higher. One of the mummified bodies in the museum, displayed with his rifle, is reputed to be the remains of a powerful local guerrilla commander who was captured and sH๏τ by an army firing squad at the height of the Cristero rebellion.

Leave a Reply