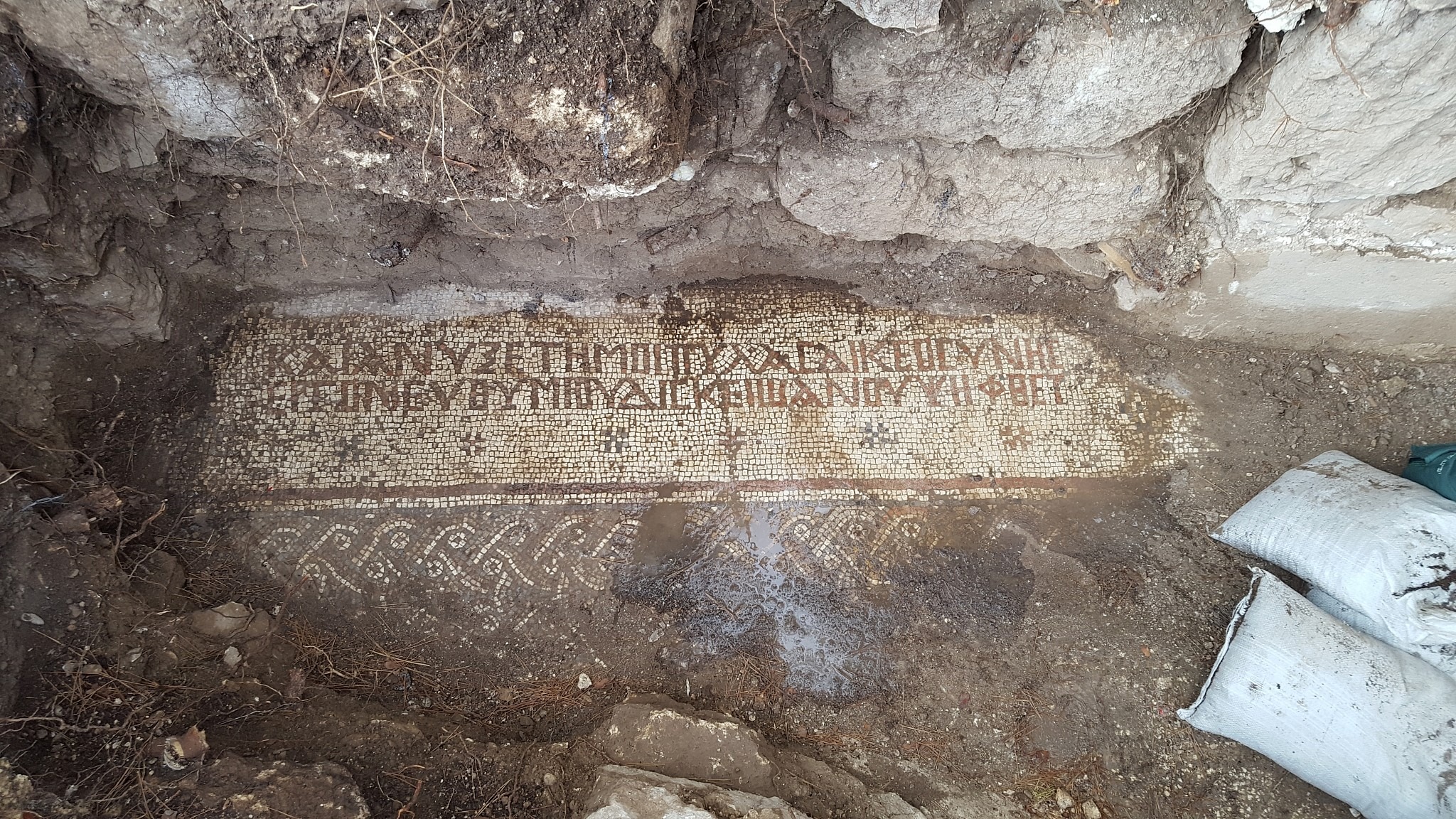

A newly uncovered mosaic in the western Galilee speaks to the relatively high status of women in the early Church. Dating to the 5th century, a Greek-language inscription memorializes one “Sausann” (or Shoshana) as a donor for the construction of a village church. It is one of seven inscriptions — including a massive five-meter long text — which were found in three Byzantine churches during this summer’s excavations by Kinneret College archaeologist Mordechai Aviam and historian Jacob Ashkenazi.

Unusual in a patriarchal society, the donor Sausann is credited in the inscription independently of any spouse or male guardian. This Sausann is thought to have been a woman of some standing, perhaps following in the footsteps of her presumed namesake, the female disciple Susannah, who was among the women named in Luke 8:3 who provided for Jesus “out of their resources.”

The find buttresses the position taken by a growing number of early church scholars that women played an important role in its foundation. According to a recent article in Christianity Today, “in the upper echelons of society, women often converted to Christianity while their male relatives remained pagans, lest they lose their senatorial status. This too contributed to the inordinate number of women in the church, particularly upper-class women.”

The idea of an independent women of means in rural Western Galilee came as a surprise to archaeologist Aviam, who heads the Institute for Galilean Archaeology. He said in a recent Haaretz article, “She’s an independent woman who donated money to the church, which says something about life in the Galilean village.”

Co-directors of the Galilee early church excavations at their recent dig site, historian Jacob Ashkenazi and archaeologist Mordechai Aviam from the Kinneret Institute for Galilean Archaeology at the Kinneret Academic College (courtesy, Mordechai Aviam)

With a three-year grant from the Israeli Science Foundation, the researchers are taking a cross-disciplinary approach to complete the first serious, modern study of Christian Galilee in late Antiquity, Aviam told The Times of Israel on Monday. Working in tandem, the rare multidisciplinary partnership of scholars is drawing from their respective fields to paint a comprehensive picture of 4th-5th century Christian life in the region.

They have already “hit the jackpot” in their first season, with seven lengthy 1,600-year-old Greek inscriptions, said Aviam. (For fear of vandals, their exact locations are being withheld.)

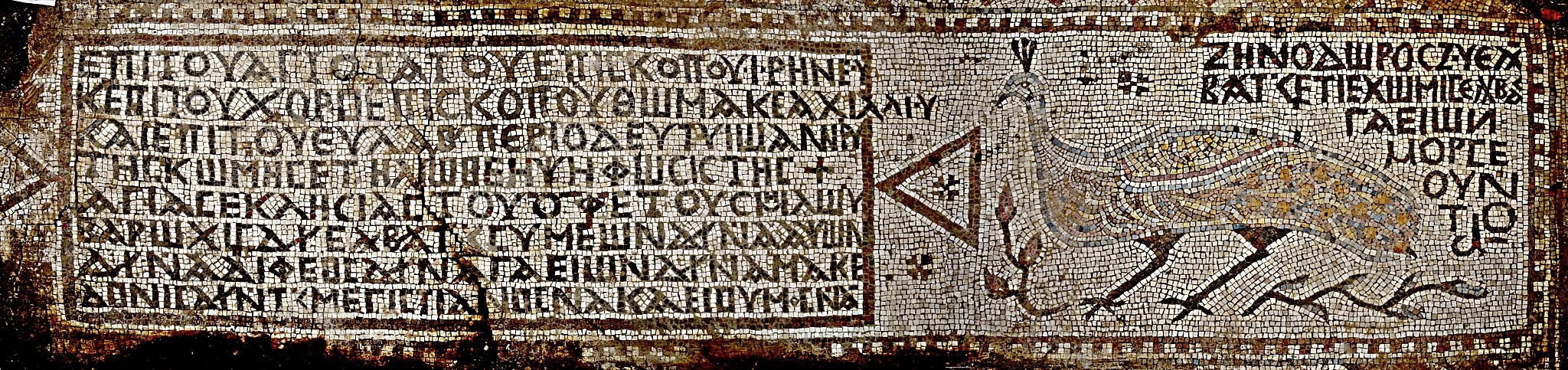

Decorated with a peacock, the five-meter long Greek inscription is the largest found in the area. It is also, inadvertently, another testament to a woman in Jesus’ life.

A peacock adorns this 5-meter long Greek inscription naming the archbishop of Tyre found west of the Sea of Galilee, in the summer of 2017, in an excavation co-directed by historian Jacob Ashkenazi and archaeologist Mordechai Aviam. (Yehoshoa Dray)

Irenaeus, named in the mosaic as the bishop of Tyre upon the church’s completion in 445 CE, was a friend of Nestorius, a controversial leading figure in 5th century Christendom. Nestorius was vilified for speaking against the “Theotokos,” the philosophy that Jesus’s mother Mary was the “God-bearer.” Instead, he promoted a radical idea that she gave birth to a human who was divine.

This ideological conflict laid ground for a decades-long battle and eventual schism in the Byzantine period church. Associates of Nestorius such as Irenaeus saw their fates rise and fall alongside their friend.

Until the discovery of the mosaic this summer, it was unclear in which year Irenaeus was ordained as bishop of Tyre. According to the 2011 anthology, “Episcopal Elections in Late Antiquity,” a date of circa 445 is often given. However, since he was historically thought to be exiled along with Nestorius to Petra for 12 years in 436 — “along with two horses to carry their luggage” — the authors present a strong case for a later date.

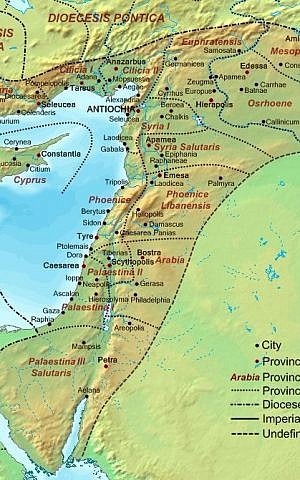

The newly discovered mosaic, whose inscription provides the date of the church’s completion as 445, accords Irenaeus the title of “episkopos” or bishop of Tyre, capital of Phoenice. The clear historical proof puts an old academic controversy to rest and gives credence to a date as early as 444 CE for his ordination. By 449 CE, he had been deposed.

This inscription is a “great opportunity to connect the name on the mosaic, with that from the history books,” said Aviam.

The people behind the inscriptions

According to Aviam, much can be learned through the inscriptions about the villagers who commissioned the mosaics.

Written in Byzantine period Greek, they are “full of mistakes in Greek,” he said. For example, an inscription of Psalm 118:19, “Open to me the gates of righteousness,” has several discrepancies from the text redacted in the Greek translation of the Bible, the Septuagint.

“They are local people,” said Aviam, “who probably couldn’t bring the best artists, and as a result one sees many mistakes.” For the most part, the names listed in the inscriptions are of local people, mostly of Greater Syrian origin, and some with a marked Phoenician influence.

There are indications that the villagers were originally pagan converts, said Aviam. “They don’t have ‘Jewish’ names, which tells us that if they were Jews that converted to Christianity, they likely changed their names,” he said.

But beyond their names, there are other reasons why the archaeologist believes the villagers were originally pagan, including the types of pottery found onsite, as well as remnants of pagan temples.

A Greek inscription of Psalm 118:19, ‘Open to me the gates of righteousness,’ also has the name of the artist. (courtesy Mordechai Aviam)

“In one church we had three pedestals which were reused in the building of the church in the walls,” he said. One had an image within a wreath, which for archaeologists is a very clear sign of pagan influence, he said. On the top of each pedestal were four holes, which were probably used to hold sculptures — not an adornment used in churches or synagogues, rather in pagan temples.

Since the temple pieces were only reused in the building of the church which was consecrated in 445, Aviam assumes the villagers were pagans until sometime in the 4th or 5th century, he said.

At the same time, Aviam is impressed with how quickly Christianity reached rural Galilee, following the formal adoption of the religion by the Byzantine empire in 380 CE, saying it pointed to a Christianization of the rural Galilee area starting from the very beginning of the 5th century.

In addition to Bishop Irenaeus, other insights into church hierarchy are gleaned from the inscriptions. Listed names include deacons and a special bishop who wandered among the villages to answer religious problems, as well as another bishop who was responsible for their economic resources.

“We were very lucky to find this and got a lot of information to start building the map of Christian Byzantine Galilean society, economy and religious hierarchy,” said Aviam.

The importance of conservative excavation

Archaeological evidence such as stone vessels and coins “tell us a little bit of history, but what is the meaning of such and such vessels in such and such site is a matter for a lot of interpretation,” said Aviam. “Finding inscriptions is like finding a book — it gives a clear history.”

The churches’ inscriptions, said Aviam, “tell the stories of who built the church and when, the church hierarchy, names of donors… they give us a lot of information.”

Since it is information they are after, the team carefully sources its dig sites and pinpoints exactly which portions should be excavated.

After decades of fieldwork, Aviam said he can “see a church’s plan from the surface.” While walking among ancient sites known to have been inhabited during the Byzantine period, he said he is able to identify churches through their ruins’ outlines.

View of the floor plan of the Byzantine-era church discovered near Abu Ghosh during the upgrading and expansion of the Jerusalem-Tel Aviv highway, June 2015. (Skyview, courtesy of Antiquities Authority)

He explained that as opposed to contemporary period synagogues which are oriented north-south, Byzantine church buildings are oriented west-east.

“On the eastern side, if we’re lucky, we can see the apse, a semi-circular wall where the altar was standing. Sometimes there are pillars, still-standing or laying down,” said Aviam, which aid in identification to a 99 percent certainty, he said.

Once a church has been identified, the team pinpoint excavates in areas of the structure in which inscriptions are typically found. After seeing the results at a number of digs of similar churches throughout Israel, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan and Turkey, archaeologists know that they are usually in front of the main apse or side apse, in front of the entrances, main, and side, and sometimes in the center of the building, said Aviam, who decided to excavate his structures in that order.

“In the first week, we hit the jackpot. Not all of the places [had inscriptions], but in every church, we found one to four inscriptions,” he said.

Aviam, who will publish the team’s findings at the end of its three-year grant, said they also dug some other parts of the structures to ascertain an exact building plan, but attempted to keep its excavation work to a minimum.

“When we dig and uncover a site, it’s a stage in the destruction of the building,” he said. “So we excavated small areas to be more ethical. We preserved more — and lost less money.” Whatever was excavated was re-covered, in accordance to the Israel Antiquities Authority license the team was granted.

“We don’t like to excavate everything,” he said. “We want to preserve things for future generations who will be smarter than we are today.”

Leave a Reply