By K. Kris Hirst

Updated on September 30, 2019

Xerxes (518 BCE–August 465 BCE) was a king of the Achaemenid dynasty during the Mediterranean late Bronze Age. His rule came at the height of the Persian empire, and he is well-documented by the Greeks, who described him as a passionate, cruel, self-indulgent womanizer—but much of that may well have been slander.

Early Life

Xerxes was born about 518–519 BCE, the eldest son of Darius the Great (550 BCE–486 BCE) and his second wife Atossa. Darius was the fourth king of the Achaemenid empire, but not directly descended from the founder Cyrus II (~600–530 BCE). Darius would take the empire to its greatest extent, but before he could accomplish that, he needed to establish his connection to the family. When it came time to name a successor, he chose Xerxes, because Atossa was a daughter of Cyrus.

Scholars know Xerxes primarily from Greek records pertaining to a failed attempt to add Greece to the Persian Empire. Those earliest surviving records include a play by Aeschylus (525–456 BCE) called “The Persians” and Herodotus’ “Histories.” There are also some Persian tales of Esfandiyar or Isfendiyadh in the 10th century CE history of Iran known as the “Shahnameh” (the “Book of Kings,” written by Abul-Qâsem Ferdowsi Tusi). And there are Jewish stories about Ahausuerus from as early as the 4th century BCE in the Bible, particularly the Book of Esther.

Education

There are no surviving records of Xerxes’ specific education, but the Greek philosopher Xenophon (431–354 BCE), who knew Xerxes’ great-grandson, described the main features of a noble Persian’s education. The boys were taught in the court by eunuchs, receiving lessons in riding and archery from a young age.

Tutors drawn from the nobility taught the Persian virtues of wisdom, justice, prudence, and bravery, as well as the religion of Zoroaster, instilling a reverence to the god Ahura Mazda. No royal student learned to read or write, as literacy was relegated to specialists.

Succession

Darius selected Xerxes as his heir and successor because of Atossa’s connection to Cyrus, and the fact that Xerxes was the first son born to Darius after he became king. Darius’ eldest son Artobarzanes (or Ariaramnes) was from his first wife, who was not of royal blood. When Darius died there were other claimants—Darius had at least three other wives, including another daughter of Cyrus, but apparently, the transition was not strongly contested. The investiture may have taken place at Zendan-e-Suleiman (Solomon’s Prison) at Pasargadae, a sanctuary of the goddess Anahita near the hollow cone of an ancient volcano.

Gateway of All Lands, erected by Xerxes in the 5th Cent. BC in the ancient Persian city of Persepolis. Dmitri Kessel / Getty Images

Darius had died abruptly, while he was preparing for war with Greece, which had been interrupted by the revolt of the Egyptians. Within the first or second year of Xerxes’ rule, he had to quell an uprising in Egypt (he invaded Egypt in 484 BCE and left his brother Achaemenes governor before returning to Persia), at least two uprisings in Babylon, and perhaps one in Judah.

The Greed for Greece

At the time Xerxes achieved the throne, the Persian empire was at its height, with a number of Persian satrapies (governmental provinces) established from India and central Asia to modern Uzbekistan, westward in North Africa to Ethiopia and Libya and the eastern shores of the Mediterranean. Capitals were established at Sardis, Babylon, Memphis, Ecbatana, Pasargadae, Bactra, and Arachoti, all administered by royal princes.

Darius wanted to add Greece as his first step into Europe, but it was also a grudge rematch. Cyrus the Great had earlier tried to capture the prize, but instead lost the Battle of Marathon and suffered the sack of his capital of Sardis during the Ionian Revolt (499–493 BCE).

Greco-Persian Conflict, 480–479 BCE

Xerxes followed in his father’s footsteps in what the Greek historians called a classic state of hubris: he was aggressively certain that the Zoroastrian gods of the mighty Persian empire were on his side and laughed at Greek preparations for battle.

After three years of preparation, Xerxes invaded Greece in August of 480 BCE. Estimates of his forces are ridiculously overblown. Herodotus estimated a military force of some 1.7 million, while modern scholars estimate a more reasonable 200,000, still a formidable army and navy.

Leonidas at the Battle of Thermopylae. Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825), Musee du Louvre. G. DAGLI ORTI / De Agostini Picture Library / Getty Images Plus

The Persians crossed the Hellespont using a pontoon bridge and met a small group of Spartans led by Leonidas on the plain at Thermopylae. Vastly outnumbered, the Greeks lost. A naval battle at Artemision proved indecisive; the Persians technically won but took heavy losses. At the naval battle of Salamis, though, the Greeks were victorious under the leadership of Themistocles (524–459 BCE), but in the meantime, Xerxes sacked Athens and torched the Acropolis.

After the disaster at Salamis, Xerxes installed a governor in Thessaly—Mardonius, with an army of 300,000 men—and returned to his capital at Sardis. At the Battle of Plataea in 479 BCE, however, Mardonius was defeated and killed, effectively ending the Persian invasion of Greece.

Building Persepolis

In addition to the complete failure to win Greece, Xerxes is famous for building Persepolis. Founded by Darius about 515 BCE, the city was the focus of new building projects for the length of the Persian empire, still expanding when Alexander the Great (356–323 BCE) set upon it in 330 BCE.

Buildings constructed by Xerxes were specifically targeted for destruction by Alexander, whose writers nevertheless represent the best descriptions of the damaged buildings. The citadel included a walled palace area and a colossal statue of Xerxes. There were lush gardens fed by an extensive canal system—the drains still work. Palaces, the apadana (audience hall), a treasury and entrance gates all graced the city.

Relief Sculpture on Apadana Stairway at Persepolis

The terrace at Persepolis is carved with figures bringing tributes to the Achaemenid king and large tables which depict a lion attacking a bull. Corbis / Getty Images

Marriage and Family

Xerxes was married to his first wife Amestris for a very long time, although there’s no record of when the marriage began. Some historians argue that his wife was chosen for him by his mother Atossa, who selected Amestris because she was the daughter of Otanes and had money and political connections. Together they had at least six children: Darius, Hystapes, Artaxerxes I, Ratahsah, Ameytis, and Rodogyne. Artaxerxes I would reign for 45 years after Xerxes’ death (r. 465–424 BCE).

They stayed married, but Xerxes built an enormous harem, and while he was in Sardis after the Battle of Salamis, he fell in love with the wife of his full brother Masistes. She resisted him, so he arranged a marriage between Masistes’ daughter Artayne and his own eldest son Darius. After the party returned to Susa, Xerxes turned his attention to his niece.

Ametris learned of the intrigue and, assuming it had been arranged by Masistes’ wife, she mutilated her and sent her back to her husband. Masistes fled to Bactria to raise an insurrection, but Xerxes sent an army and they killed him.

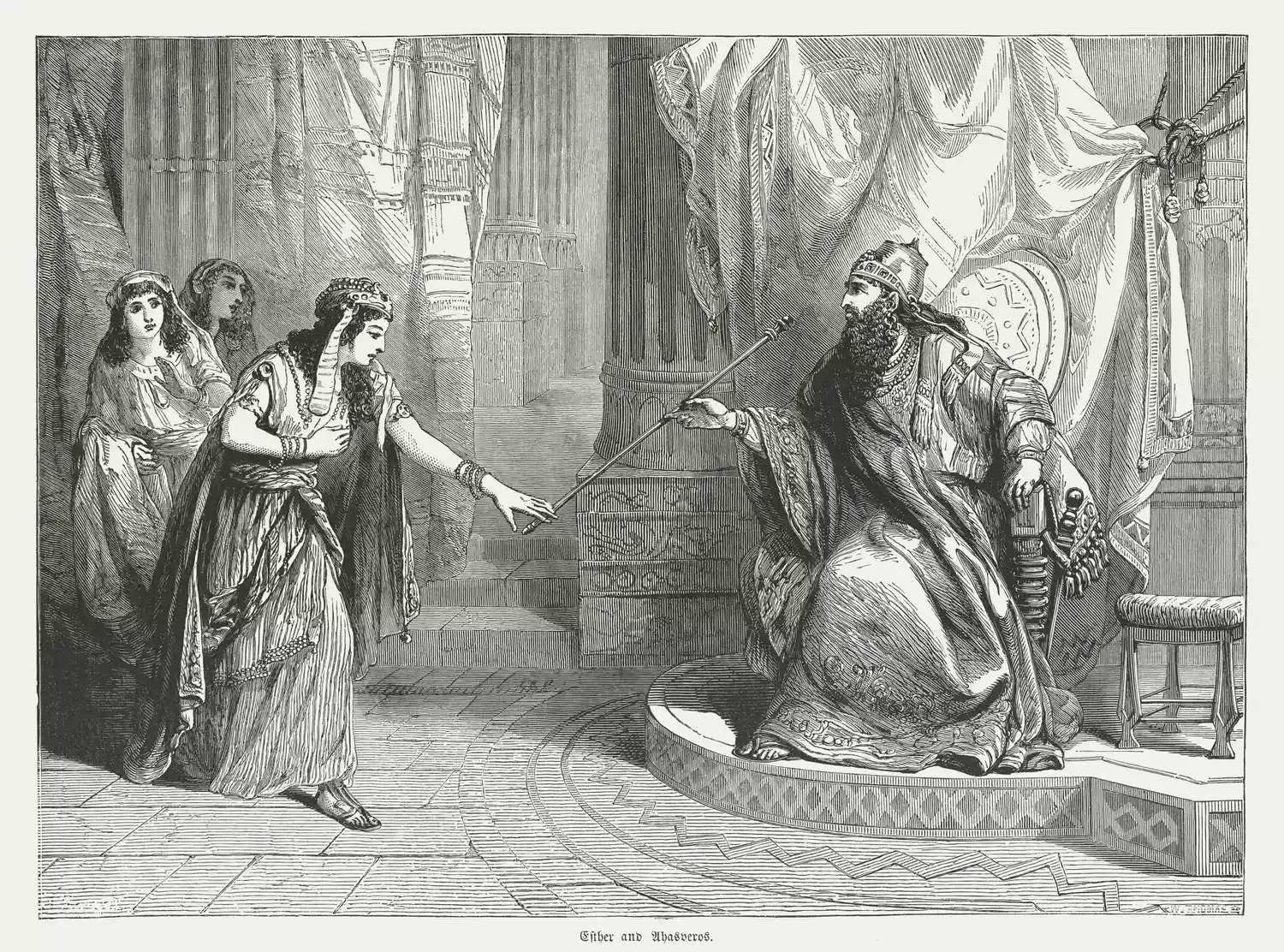

Esther and Ahasuerus

Queen Esther standing in the court of Ahasuerus: the king holds out to Esther the golden scepter that was in his hand. (Esther 5, 2). Wood engraving, published in 1886. DigitalVision Vectors / Getty Images

The book of Esther, which may be a work of fiction, is set in Xerxes’ rule and was written about 400 BCE. In it, Esther (Asturya), the daughter of Mordecai, marries Xerxes (called Ahasuerus), in order to foil a plot by the wicked Haman who seeks to organize a pogrom against the Jews.

Death of Xerxes

Xerxes was slain in his bed at Persepolis in August 465 BCE. The Greek historians generally agree that the murderer was a prefect named Artabanus, who aspired to assume Xerxes’ kingship. Bribing the eunuch chamberlain, Artabanus entered the chamber one night and stabbed Xerxes to death.

After killing Xerxes, Artabanus went to Xerxes’ son Artaxerxes and told him that his brother Darius was the murderer. Artaxerxes headed straight to his brother’s bedchamber and killed him.

The plot was eventually discovered, Artaxerxes was acknowledged as king and successor to Xerxes, and Artabanus and his sons were arrested and killed.

Persian Empire Tombs of Naqsh-e Rostam, Marvdascht, Fars, Iran, Asia

The Achaemenid Tombs of Naqsh-e Rostam including that of Xerxes, Marvdascht, Fars, Iran, Asia. Gilles Barbier / Getty Images

Legacy

Despite his fatal errors, Xerxes left the Achaemenid empire intact for his son Artaxerxes. It would not be until Alexander the Great that the empire was disassembled into pieces ruled by Alexander’s generals, the Seleucid kings, who ruled unevenly until the Romans began their ascendancy in the region.

Leave a Reply